![]()

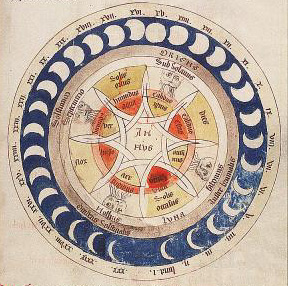

Metaphors from Birth to Death in the Phases of the Moon:

How Ancient Astrology Viewed the Lunar Cycle

by Dorian Gieseler Greenbaum, M.A. ©1999, revised July 2002

The ancients were in tune with the Moon in a way that has been lost in our light-polluted, computer-centric world. Many of us don’t observe the Moon’s position in the sky every single night (we are great Ephemeris readers!), and our lives in terms of light and dark no longer depend on having moonlight at night. The physical moon is only a natural curiosity, and the astrological Moon thus becomes symbolic of a physical reality that isn’t very present in modern life.

Ancient astrologers, with their far more immediate observation of the Moon, could bring this power of observation to their astrological interpretations. The Moon was a living, visible image whose physical characteristics provided instant astrological description. With its cycle of growth and decay, it furnished a clear analogy to life on earth. The Moon is called “fortune” (something which goes up and down!) by more than one ancient author. It basks in the reflected light of the Sun, and its phases (literally, “appearances” in Greek) are dependent upon its relationship to the Sun.

Many ancient authors discuss the phases of the Moon. In this article, I will be discussing the works of two in particular, Paulus Alexandrinus (378 C.E.) and Olympiodorus (564 C.E.), because they go beyond mere definition of each phase. The material of these writers gives a fascinating picture of how the Hellenistic Greeks viewed the cycle of the Moon. As modern people, we can learn a lot from seeing how these ancient astrologers thought about the Moon as it moved in its circular dance with the Sun.

It isn't always easy to figure out what the ancient writers are saying, but like a crossword puzzle, we can seek out clues from the language used by the Greeks as they describe the appearances of the Moon. Even the simple word phasis, which becomes “phase” in English, can give us information. For the Greeks, phases are literal “appearances;” the word phasis comes from the verb phainō, to appear. Each appearance heralds a new scene, with new information ready to be given to us by the changing Moon.

What is the Moon saying to us as she makes these different appearances? We can find out in the words the Greeks use to describe each phase. Let’s look at each phase, and the words used to describe it, in detail. Analogies to the birth process are very clear in the first several phases. Though the Greek authors did not carry this birth analogy further than the first crescent phase, I find it productive to continue looking at these phases, and the words used to describe them, as the cycle of human growth and development. Following a discussion of the phases, I will suggest ways in which we, in the modern world, can use the meaning of each phase in our own lives. In this way we can take the material of the Hellenistic astrologers and apply it in a new way to the present day.

By the way, Paulus and Olympiodorus describe 11 phases of the Moon in their treatises, not the usual 8 we are used to. In the discussion that follows, I will refer to the phases by number as well as by the names they used for each phase. You will see that the “extra” phases the Greeks use are, in fact, quite instructive for us in understanding their view of the lunar cycle as a cycle of birth.

Note: All translations of the Greek are the author’s.

Phase 1 – New Moon, Synodos. Our modern term is “conjunction.” Astronomically, a synodic cycle goes from New Moon (exact conjunction of Moon and Sun; that is, the Moon and Sun are at the same zodiacal degree) to New Moon. Unlike the word “conjunction,” which means “join together,” synodos actually means “with the path” in Greek. Paulus refers to the synodos as the “coming together” (sunienai) of the Moon to the Sun and running along the same path with it.[1]

What path can this be? Maybe Lovers’ Lane! For Olympiodorus takes Paulus’ description of the synodos and elaborates on it. He makes a play on words by using the verb which means “to bind together” (sundeō) and the verb which means “to travel in company with” (sunodeuō). He says: “For [the Moon] has been bound (sundeō) with the Sun under these circumstances by travelling along (sunodeuō) with it, whence the astrologers call this phase a concurrent bond (sunodikos sundesmos).”[2]

And what is

this bond, this joining together of the Sun (certainly an archetypal male

principle) with the Moon (female)? It

is clearly, as we see from the descriptions of the next two phases, a union

that results in birth. Let’s call it

“conception.”

Phase 2 – Coming

Forth, Genna. Modern astrologers do not normally

acknowledge this phase. It occurs when

the Moon has moved to the degree after the exact conjunction, and continues up

until it has reached 15 degrees after the conjunction. (Those readers with a

knowledge of astronomy know what happens when the Moon moves 15 degrees beyond

the Sun: it heliacally rises and has its first visibility to us! This will become significant as we describe

the phase following genna.)

Genna

has a few meanings, among them “begetting,” “engendering,” “descent,”

“origin” and “birth.” It is related to

the verb gennaō, which in one

form[3]

means “to cause to become,” and thus “beget.”

Its translation in the Greek Lexicon[4]

as a phase of the Moon is given as “Coming Forth.” When we combine these two meanings, “begetting” and “coming

forth,” it is easy to imagine a baby in

the process of being born. Let’s look

at the words of Paulus and Olympiodorus as they describe this phase.

Paulus says, “Coming Forth was so

called from the Moon’s going out from the Sun, since when she has gone beyond

it by one degree, she begins to appear to the Cosmos, though not to us.”[5] Olympiodorus again elaborates on the words

of Paulus with some stunning imagery: “...the phase is said [to be] Coming

Forth, since it passes by the bowels of the Sun. And under these circumstances it proceeds from the unseen into

the visible, after the manner of fetuses.”[6]

The birth imagery is undeniable in

this quote from Olympiodorus. The word

“bowels,” koilia in Greek, refers to

the cavities of the body, and can refer to both the bowels and the womb! (Rob Hand points out that this word in Greek

has the same equivalent meanings as our English word “belly.”) So the Moon and Sun come together in the

moment of conception (the synodos)

and then the Moon moves beyond the bowels, or womb, of the Sun.[7]

We can easily equate this with the

portion of the birth process known as labor, when the baby moves down the birth

canal but has not yet been born. The

Moon, when it moves past the Sun by one degree, is no longer joined but is

still invisible. It is “coming forth,”

but has not yet emerged from the light of the Sun. We will see this happen in the next phase.

Phase 3 – Emergence,

Anatolē. When the Moon has moved 15 degrees beyond the Sun, until it

reaches 60 degrees, it is called anatolē,

“Rising.” What, you may ask, does “rising” have to do with birth? If we examine the origins of this word, a

much more illuminating translation comes to light, one that beautifully shows

its connection with the birth process.

Anatolē

comes from the verb anatellō,

which is a compound verb formed from the preposition ana, “up” and the root tellō. This root is related to a verb that means to

accomplish, perform or produce, and also has the sense of “come into being.”[8] Combining the two, we have “come up into being,” or, of stars,

“rise.”

But what does it mean for a star to

rise? When stars rise above the

horizon, or go far enough past the Sun (beyond 15 degrees!) they become visible

to us. So rising is associated with

visibility to us.

In keeping with the birth analogy, anatolē is the phase where the baby

appears to us; it “emerges” from the darkness of the birth canal. Instead of translating anatolē as “rising,” I prefer to use the word “emergence.” The roots of the Latin-derived “emerge” mean to “come out a

sunken condition, come forth, rise up.”

Paulus says, “Emergence is whenever, having gone past 15 degrees, [the

Moon] appears to take on light as a slender line.”[9] We now have the appearance of the body in

the physical world.

Phase 4 – First Crescent, Mēnoeidēs. This phase corresponds to our “Waxing Crescent” Moon. It begins at the waxing sextile (the Moon is 60 degrees ahead of the Sun), when the Moon has grown into its familiar crescent shape. In the Greek name of this phase, we can see an interesting connection between “moon” and “month” (even in English, we can see the semantic similarity). In the ancient world, the month was originally the time elapsed from New Moon to New Moon (or when the first sliver of the Moon was visible), and in Greek the word for month (meis, mēnos) can also mean moon (mēnē). At the beginning of the lunar month, the shape of the Moon at first visibility was the crescent, so the word mēnoeidēs came to mean the shape of the crescent (crescent comes from the Latin, meaning “growing”). In Greek, though, it actually means “moon-form,” and Paulus says “it appears to take on the shape like itself.” (Chapter 16, p. 35, ll. 3-4) Olympiodorus adds: “...it receives its familiar form and its own disc, just like a shadow-painting.” (Chapter 15, p. 26, ll. 8-10)

The use of the phrase “shadow-painting” is interesting, because it emphasizes the use of light and dark, which in turn accentuates the the gradual illumination of the (dark) disc of the Moon by the light of the Sun. And let’s consider the phrase “receives its familiar form.” The Moon is now recognizable as the Moon. The word translated as “receive” literally means to take from another, or receive what is one’s due. Here we have the idea of genetic inheritance, in that the fetus receives what it is ordained to get from its parents. When we consider that the word “familiar” actually means having to do with the family, we can equate this phase with the growth of the baby as it takes on the features of its familial inheritance and becomes recognizable as a member of a certain family. (Every parent and grandparent looks for these familial features! “Oh, look! He has your mother’s eyes!”) We should also consider that this phase, the waxing sextile, may be the calm before the storm of adolescence (the next phase).

Phase 5 – First Half-Moon, Dichotomos. We are midway between the New Moon and the Whole Moon— 90 degrees from both (what moderns call "First Quarter"). The Half-Moon occurs when the Moon is in square to the Sun, squares being described by Paulus as “discordant and irregular.” p. 24, l. 10 This phase is called literally, “Cut in Two,” because the disc of the Moon appears to be cut in half. Olympiodorus says, “half of the disc appears illuminated and half unlit.” p. 26, ll. 14-15

Though Paulus and Olympiodorus do not take this analogy further, isn’t this a wonderful description of adolescence? Teenagers know everything, and they know nothing. They are separating from their parents and developing their own character, a portion of which is not yet apparent. This is a time of almost literal dichotomy — sweet one day, ogres the next, full of mood swings and uncertainty.

Phase 6 - Amphikurtos, First Gibbous. This phase occurs when the Moon has moved 120 degrees away from the Sun, forming a trine (triangle) with it. Amphikurtos means “humped or swollen on both sides.” We are not yet at the Whole Moon, but its shape has moved beyond the half-circle. (By the way, “gibbous” comes from Latin gibbosus, which means “humped.”)

We are beyond the turmoil of adolescence and into young adulthood. We can relate to our parents again in a non-adversarial way (we may even realize they have some wisdom to impart!). We are secure enough in our own sense of self to acknowledge that others will not destroy our identity, but in fact may enhance it. We are ready to embrace what the world has to offer, on the way to filling ourselves up (“rounding out the circle”) with the experiences and knowledge we need to fulfill our life’s path. Olympiodorus says that “the Moon begins to fill up its two peaks…” (p. 26, l. 21) The word for peaks in Greek is ta akra, which literally means “the heights” (the Acropolis is the high spot in Athens). Young adulthood is usually an exciting time, filled with new experiences and a heady rush of independence, a period of “highs,” especially after the angst of adolescence.

Phase 7 – Full Moon, Plēsiselēnos. The Moon is between gibbous and whole; as Olympiodorus says, “...a Full Moon...since it is neither a full whole moon, nor gibbous, yet truly both.” p.28, ll. 10-12 We are on the edge of maturity here: past the trine but not yet at the opposition, still in the gathering, waxing phase. There is some uncertainty about this phase, too. We can not clearly tell when the exact moment of the whole moon is; sometimes when we look quickly at the moon around wholeness, we can not always see the difference between the very gibbous (full to Paulus and Olympiodorus) and full (whole to Paulus and Olympiodorus). Maturity is like that, too. When do you know you are mature? (Often it’s only in hindsight, and we usually see it as a process, not a moment.) So now we move past the “full” and into:

Phase 8 – Whole Moon, Panselēnos. This is 180 degrees from the New Moon (Synodos) and continues until 15 degrees past the exact opposition (matching the description of Anatolē occurring at 15 degrees past the conjunction). Paulus describes it in this way: “Whole Moon because it has been filled with the light from the beams of the Sun,...having the whole brightness of the light filled up, whence, when it has become a Whole Moon, it appears itself in the form of a circle like the Sun’s.” p. 35, ll. 10-14

There are a number of analogies we can make with this phase. Clearly, in the description of the Whole Moon “in the form of a circle like the Sun’s” we have another form of union—not conception this time, but marriage. Alternatively, in this phase we come to the realization of life’s purpose, and the means to go about achieving it. We are still in process here, for like the full moon phase, it is sometimes difficult to tell the exact moment of wholeness. Like the Synodos, we are aware of the moment of opposition only after it has passed. Likewise, we see our maturity only in hindsight.

It is after our realization of the point of opposition that we become aware that the Moon is now waning. Apokrousis, “waning,” literally means “beating off” or “driving away,” with the sense of repelling or refuting. Does the Sun now begin to drive away the Moon? We are now moving slowly away from the light into the darkness. We have passed from the 7th sign into the 8th, and we become increasingly aware of our mortality. The Moon moves past its point of perfect roundness, and toward:

Phase 9 – Second Gibbous, Second Amphikurtos. This is the waning trine, with the Moon now 120 degrees behind the Sun. We are continuing the completion of our life’s work, using the skills and knowledge we have gained, and acquiring the beginning of wisdom. Olympiodorus talks about the waning phases as repeating the same aspects which occurred in the waxing part of the cycle: “…it experiences the same figures again.” (Ch. 15, p. 27) We could make the analogy that the waxing trine was a phase where we were “filling ourselves up” with knowledge, and that the waning trine becomes a period in which we begin to give knowledge away to others.

Phase 10 – Second Half-Moon, Second Dichotomos. The waning square ("Last Quarter") again becomes a crisis point, as the waxing square, adolescence, was. The intimations of mortality become more and more clear, so we begin putting together the proofs of our life’s work and melding them into the wisdom combined from our learning and experience. This task culminates in:

Phase 11 – Second Crescent, Second Mēnoeidēs. The Moon is 60 degrees, or a waning sextile behind the Sun. Now we achieve our swan song, which shows finally the fruits of our purpose to the world. Now we have finished what it was we were meant to do. We are ready now to return without fear to the darkness which gave us birth. Our purpose is complete.